31 Mar Painting’s Doubt

Nine days out of ten all he saw around him was the wretchedness of his unsuccessful attempts.

Nine days out of ten all he saw around him was the wretchedness of his unsuccessful attempts.

— Maurice Merleau-Ponty

Professor Matt Saunders offers Harvard undergrads an unusual studio course he titles “Painting’s Doubt.”

“Painting is an engagement between the self and the world,” his course description reads. “It is a practice of embodied making.”

Saunders’ ambiguous course title no doubt refers to the way a painting instructor will teach you to doubt “conditioned understanding” and “to see like an artist”

But it also refers to the fact that painting is doubt.

It’s all about doubt.

Saunders’ course title in the latter sense echoes the title of Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s pivotal essay “Cezanne’s Doubt.”

“It took him one hundred working sessions for a still life, one hundred-fifty sittings for a portrait,” the essay on Cezanne opens. “What we call his work was, for him, an attempt, an approach to painting.”

For all his skill and commitment to craft, Cezanne was never pleased with his paintings.

He was a creature plagued by doubt, Merleau-Ponty says.

“Painting was his world and his mode of existence. And still he had moments of doubt about this vocation.”

Cezanne’s uncertainty stemmed not from a neurosis—although he was, as his companions well knew, exceedingly neurotic—but from “the purpose of his work,” which he believed was to depict nature “in God’s eyes.”

“Cezanne’s difficulties are those of the first word,” Merleau-Ponty says. “He thought himself powerless because he was not omnipotent, because he was not God and wanted nevertheless to portray the world, to change it completely into a spectacle.”

Instead Cezanne, wracked with doubt, discovered over and over again that he couldn’t achieve his purpose.

He couldn’t impose his will on his work.

“It was from the approval of others that he had to await the proof of his worth,” Merleau-Ponty says. “That is why he questioned the picture emerging beneath his hand, why he hung on the glances other people directed toward his canvas. That is why he never finished working.”

Painting, as I see the craft, is all about doubt.

You doubt your eye.

You doubt your hand.

You doubt your paints, your brushes, your setup and—sometimes—your sanity.

You doubt the painting you’re working on will ever turn out; and should you manage to pull it off, you doubt you’ll ever pull off another.

Doubt, no doubt, comes with the territory.

“The greater the artist, the greater the doubt,” the art critic Robert Hughes said of Cezanne.

“Perfect confidence is granted to the less talented as a consolation prize.”

HAT TIP: Thanks go to painter Rosiland Jordan for alerting me to Professor Saunders ’ course.

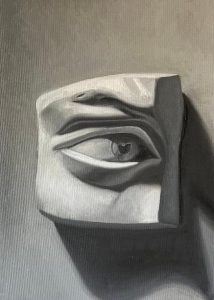

Above: Study of David’s Eye. Robert Francis James. Oil on canvas board. 11 x 14 inches.