15 Jan These Foolish Things

Why is it awful for a painter today to create an impressionist painting? It’s not because they’re painting it badly; it’s because they don’t have a reason to paint it.

— Matthew Ritchie

I sometimes hear other artists—more skilled than I—say that they’d like to paint more often, but don’t know what to paint.

Somewhere along the line, I always tell them, I received this excellent advice: Paint things with personal meaning and you’ll never get stuck.

That advice has never failed me.

At least not yet.

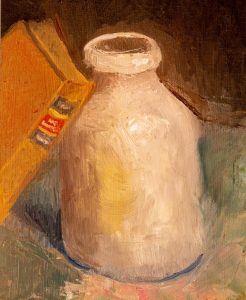

My painting Jug & Book, for example, includes a small stoneware crock, an object I love for its rough, unromantic quality.

Jug & Book also includes a small 18th-century leather-bound book that my late cousin Hank gave me when I was a kid. It reminds me of him and the lifelong love we shared for antiques. It’s a curious book, full of the rules and maxims for genteel conversation in Georgian England.

In his 1981 book The Meaning of Things, psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (the discoverer of “flow”) says domestic objects like my jug and book aren’t just collectibles, but “bridges;” time tunnels leading to the experiences that have defined our lives.

“The possessions one selects to endow with special meaning,” Csikszentmihalyi says, “are models of the self. They give tangible expression to one’s relationships, experiences, and values.”

When a painter paints an impressionist painting merely to remind us he admires the Impressionists’ work, he’s perhaps dazzling us; but her really isn’t connecting us to his life, at least not in a corporeal way.

And connecting us to his life is the whole point of painting.

Above: Jug & Book. Oil on canvas. 8 x 10 inches. Available here.